© Johnny

L. Montgomery - NYI Student

|

How to Take

Great Pictures

At the Zoo

Brought to you by:

GarLyn Zoological Park

&

New York Institute of Photography

|

|

When we

look at great photographs of animals we imagine the

romantic life of the professional photographer traveling

to faraway places, living an exotic life, and enjoying

all manner of adventures.

It's true that a lot of great animal photographs are

taken in the wild, but the fact is that many of the

greatest animal pictures are taken at the zoo! Any

pro who does a lot of animal photography will tell you

that some of their best "wild animal" pictures were

taken at the zoo.

There are several reasons why pros like working

at zoos, and these reasons are just as valid for

amateurs:

Cost and convenience:It

goes without saying that transportation costs will be

lower to get to the zoo instead of going on safari, and

you won't need medical shots or a passport.

|

© Kathy

Kinnie - NYI Student

|

Better subjects:

But cost

and convenience aren't even the best reasons. The truth

is that zoo animals are often better photographic

subjects since they live more pampered lives than their

brethren in the wilds. Many animals in the wild have

nicks and scratches covering their ears and faces -

injuries from the rough-and-tumble life that comes from

competing for food, shelter, and mates. Not so in the

zoo, where food and shelter and, often, mates are

readily provided to prevent Darwinian battles.

Better possibilities:

In the

wild you can spend days or months to find the animal you

want to photograph...and once you spot the beast you're

likely to take the picture of the animal as it is - not

necessarily as you would like it to be. If it's up in a

tree, that's where you're going to photograph it. If

it's sleeping in the brush, so be it. At the zoo you

have more possibilities to get the right "pose."

|

|

To find

the animal you want, you simply follow the printed

signs. If the animal's pose is not exactly right, you

can wait a while...or go onto something else and then

come back. You're not in a take-it-or-leave-it

situation!

Better weather:

When you

photograph at the zoo, you have the luxury of waiting

for the right weather. If it's not perfect, you can

easily come back when it's better. In the next photo you

can see how NYI student Wayne Angeloty was able to get

exactly the back-lighting he wanted, producing bright

furry outlines for these two "conversing" monkeys.

|

© Wayne

Angeloty - NYI Student

|

Safer:

Getting

close to animals in the wild can be dangerous, and many

a wildlife photographer has the scars to prove it. At

the zoo you can usually get close enough without any

risk whatsoever.

Convinced? Okay. Let's review the key points that will

help you get those great zoo photographs:

|

|

One

note of warning. We see a lot of people taunting

animals at the zoo and ignoring signs that tell them not

to feed the animals or toss objects into cages. It goes

without saying that photographers should respect these

rules, do nothing to irritate animals, and, perhaps,

even take the lead and speak up if there are people who

are ignoring the rules. Remember, a happy healthy animal

is a great photo subject. Help keep zoo animals free

from human aggravation.

Now you're going to need the right equipment. There

are two key pieces of equipment: The first is a long

zoom lens or a telephoto lens on your camera. The other

is fast (ISO 400 or higher) film. As you can see, what

you need is not very exotic.

The long lens is important because it will enable you

to make your subject large in the photo and

allow you to crop out distracting surroundings that

would detract from the subject.

Do those benefits of the long lens sound familiar?

They should. They're Guidelines Two and

Three of NYI's Three Guidelines for Better

Photographs. Guideline Two tells you to add

emphasis to the subject of your photo - the long lens

lets you do this by making your subject big so it fills

the frame. Guideline Three tells you to eliminate

anything that will distract from your subject - the long

lens does this by narrowing the field of view so very

little clutter can be seen.

What about Guideline One? It tells you to

know what you want to be the subject of your

picture before you click the shutter. In this case you

chose your subject for each photograph before you even

lifted the viewfinder to your eye. Your subject is the

animal or animals you're photographing!

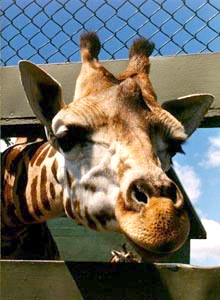

Guideline Three is particularly important

when you shoot pictures of animals in the zoo. After

all, you are usually trying to create the illusion

of the animal in the wild. Anything in your picture

that shouts "ZOO" has to be eliminated. So try to avoid

showing cage bars, zoo visitors, or signs. For example,

we think the next picture would have been more effective

if the fence weren't so obvious.

|

© Conrad

Martineau -

NYI Student

|

Why fast film? Because animals often move - and they can

move pretty fast in the zoo as well as the wild. You

usually don't want to blur your subject. With a fast

film you will be able to shoot with a sufficiently fast

shutter speed to freeze the action.

Not long ago we got a call from a photographer

lamenting that all the images he shot on a recent trip

to the zoo had come out blurred. Turns out he had used

very slow film along with a long lens that opened no

wider than f/4.5. The combination was death - it

required long exposures that resulted in camera shake

and blurred motion. Why did he use such a slow film, we

asked? He explained that in a college photography course

he once took, his teacher had warned him against using

fast film because it was too grainy.

|

Well, he

was years out of date. At NYI we tell our students not

to worry too much about grain. Because today's new film

emulsions have dramatically improved the fine grain

quality of most films - even relatively fast films, such

as ISO 400 or even 800. Our advice to you: Unless you

plan to blow up your pictures to more than 11x14, don't

worry about grain.

|

|

Here's a picture of a charging rhino taken by an NYI

student at the Los Angeles Zoo. It's awfully good. This

rhino looks like he's charging out of the Congo River,

not a zoo moat. But the image is a bit soft. Would it

make the pages of National Geographic? Probably

not because it's not 100% sharp. |

|

Why is

it soft? The photographer had no choice once he loaded

his film. He used ISO 50 slide film, which forced him to

shoot at 1/30 of a second. At this slow shutter speed

the charging rhino is slightly blurred. Had he used ISO

400 film, he could have shot at 1/250 of a second and

frozen the action. Then this picture would be worthy of

the pages of National Geographic.

Which brings us back to the question of how wide you

can open your lens. If you're using an SLR with a long

lens that has a wide (f/2.8) aperture, you can probably

get away with slower film - perhaps ISO 100 or 200. As

we'll discuss shortly, the wide-open aperture also gives

you the advantage of being able to eliminate foreground

and background clutter by using selective focus.

However, you usually don't have this luxury when you're

using a point-and-shoot camera with a zoom lens like a

35-115mm. When you're zoomed out, your lens will offer a

maximum aperture of f/8 or even f/11. Forget selective

focus. Forget a fast shutter speed. With a zoomed-out

point-and-shoot camera you need ISO 400 or faster film

just to avoid camera shake.

So much for equipment. Now, let's get to some

specific shooting tips.

Go early.

We like

to be the first ones into the zoo. Most animals are

active in the morning and there usually aren't large

groups of visitors and school kids crowding around the

animals.

Get in tight.

Whether

you're using a zoom lens or a telephoto, you'll find the

larger you can make the animal in the frame, the more

impact your photo will have. Almost all the pictures you

see here fill the frame with the face of the animal.

Use a tripod

to get

rock steady, knife-sharp images. Remember, a long lens

may force you to shoot with a slow shutter speed. Use a

tripod to avoid any possibility of camera shake.

|

© Chuck

DeLaney - NYI Dean

|

To avoid clutter - change angle.

Don't

let the amusing antics of your subject lull you into

shooting against a bad background. Remember the three

NYI Guidelines. Remember you want to create the

illusion of the wild. If you can see anything in

the viewfinder that distracts, eliminate it. Chances are

if you move just a few feet in either direction, it will

disappear.

|

To avoid clutter - use selective focus.

As we noted before, one of the advantages of a wide

aperture is that you can employ a narrow depth of field

to toss the background out of focus. This can be a real

help in creating the illusion of the wild - for

example, let's say there's a concrete background that's

designed to look like real rocks. If the background is

sharp, it looks fake and you know the animal is in the

zoo. By using selective focus, you can throw the

concrete "rocks" out of focus and make them look more

real. In the next picture, you can see how NYI student

Guy Boily used selective focus to make the ocelot sharp

while the background becomes undefinable.

|

© Guy F.

Boily -

NYI Student

|

Pick your weather.

Don't

give up just because it's cloudy. You may be able to get

better shots on a cloudy day of animals against a

background filled with glare, like water or

light-colored rocks. And if the weather's bad, you'll

probably be less concerned with crowds of visitors. In

fact, when the weather's downright "lousy," you may be

able to get some great shots - in rain or snow there

will be almost no other visitors, and the inclement

weather can create a sense of nature that helps add to

the "illusion" of the wild. Of course, there's nothing

wrong with sunny weather for these pictures; just make

sure the animals don't squint!

|

© Carla

Steckley

NYI Student

|

Flash for catch lights.

Those

small white dots in the eyes of people are part of what

give life to a portrait. Photographers call them "catch

lights." Those same catch lights give emphasis to the

eyes of animals as well. You can see them in many of the

pictures shown in this section, for example in the

picture shown to the left by NYI student Carla Steckley.

|

© Chuck

DeLaney - NYI Dean

|

Using a flash also helps photograph animals that are on

display behind glass, like the snake shown here. The

trick is to avoid the reflection of glare off the glass.

To avoid this glare, shoot at an angle through the glass

instead of head on. Remember the old angle-of-incidence

equals angle-of-reflection rule. Make sure the

reflection is thrown outside your image. If you shoot

head on, the glare will be thrown right back into the

lens - and your picture will be ruined.

|

People aren't always in the way.

There are times that the interaction of humans with

animals and vice versa tells a story in its own right.

Don't always avoid people in your photos.

Sometimes they can add a depth and dimension that

adds to the picture - for example, as in this

simple yet deeply involving photo by NYI Student Wayne

Angeloty taken in the aquarium.

|

© Wayne

Angeloty - NYI Student

|

Feeding time and other special times.

The sea lions in Central Park know when it's feeding

time and they love to perform for their keepers and for

the appreciative audiences that gather three times a

day. In many zoos there are some animals, including new

born babies, that are only on view for a limited amount

of time. Make sure you know the schedule for these photo

opportunities.

Expressions.Professional

portrait photographers often cite the "E.S.P. Rule."

That means Expressions Sell Pictures.

The same thing applies to zoo animals. If the bear is

sleeping, or just standing, or day dreaming, you don't

have as exciting a photo as you do if the bear is

growling, yawning, or otherwise active and expressing

her character.

|

If you follow our tips and visit your local zoo

frequently, you'll have a lot of fun and take lots of

great zoo photos! |

Reprinted with permission from the New York

Institute of Photography website at

http://www.nyip.com

Copyright © 2005

GarLyn Zoological Park,Inc.

Hwy 2 Naubinway, MI. 49762

(906)477-1085

www.garlynzoo.com

|